Vote Allocation

What is Vote Allocation?

Vote allocation is the process of distributing votes reported at the county (or county equivalent) level to smaller levels of geography within the county. These smaller units are almost always a precinct, but sometimes other reporting units are used (such as towns in some New England states). Vote allocation is a form of data disaggregation. Because we do not know from which precinct these votes were cast, we must estimate the share of votes reported at the county to be allocated to each precinct.

Why Allocate Votes?

Precincts are the most granular level at which most election results are available. (Individual level voter file data contains information on whether individuals vote or not, and can be used to calculate turnout, but does not contain information on which candidates voters supported.) As a result, precinct level election results are useful for analyzing maps for racial and partisan gerrymandering.

Most election results are reported by county Boards of Elections (BOE) at the precinct level, but some votes are only reported at the county level. Because the drawing or analysis of redistricting maps frequently requires knowing the geographic distribution of voters, it’s useful to know how all voters in a particular area, such as a precinct, voted. In other words, allocating county level votes to precincts ensures that all votes are captured geospatially in a precinct level shapefile.

Sometimes the distribution of votes cast at the precinct level are quite similar to those cast at the county level, but not always. The 2020 presidential election was an excellent example in which the distribution of votes cast on Election Day (and counted at the precinct level) was quite different from the absentee votes cast by mail (and counted at the county level), as can be seen on page 9 of a report by our data partner MEDSL on how we voted in the 2020 elections. When this happens, the distribution of precinct level results can look very different before and after allocation.

What Votes are Allocated?

Nearly all votes cast in person on Election Day are reported at the precinct level. Beyond that, states vary with respect to what votes are reported at the precinct versus county level. The most common type of votes that are reported at the county level and need to be allocated are:

- Absentee: ballots requested by or, in some states, automatically sent to eligible voters. This resource from NCSL outlines what absentee votes are reported at the county level in which states.

- Federal / Overseas: ballots that are requested by eligible voters living overseas at the time of the election, such as members of the military or diplomats.

- Early votes: ballots that are cast in advance of Election Day. These can be cast at a county’s election office, or a one-stop location, such as a dropbox.

- Provisional: if there is uncertainty about an in-person Election Day voter’s eligibility to cast a ballot, they may cast a provisional ballot which, with additional information or verification, will be counted.

How to Allocate Votes?

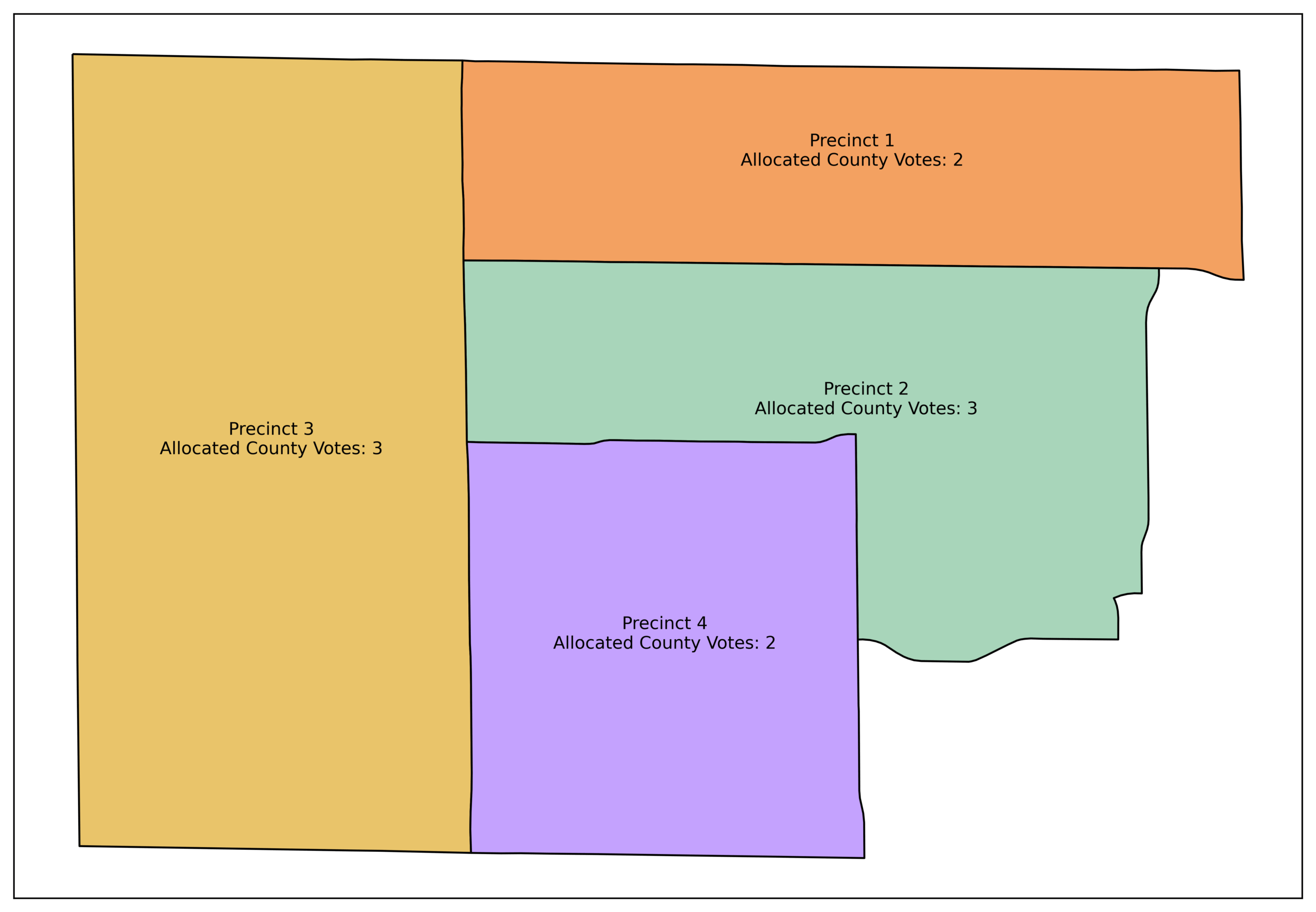

There are many ways to allocate votes. A simple, but likely inaccurate, method would be to allocate votes to all precincts evenly. For example, if a county had 10 votes to be allocated and 4 precincts, one could allocate 2 votes each to 2 precincts, and 3 votes each to the other 2 precincts.

An Example of Equal Vote Allocation

In all likelihood, however, the number of voters differs across precincts. In order to more accurately capture where votes were actually cast, votes would ideally be allocated according to how many voters in each precinct cast ballots that were ultimately counted at the county level. But if we knew this information, we wouldn’t need to estimate or perform an allocation!

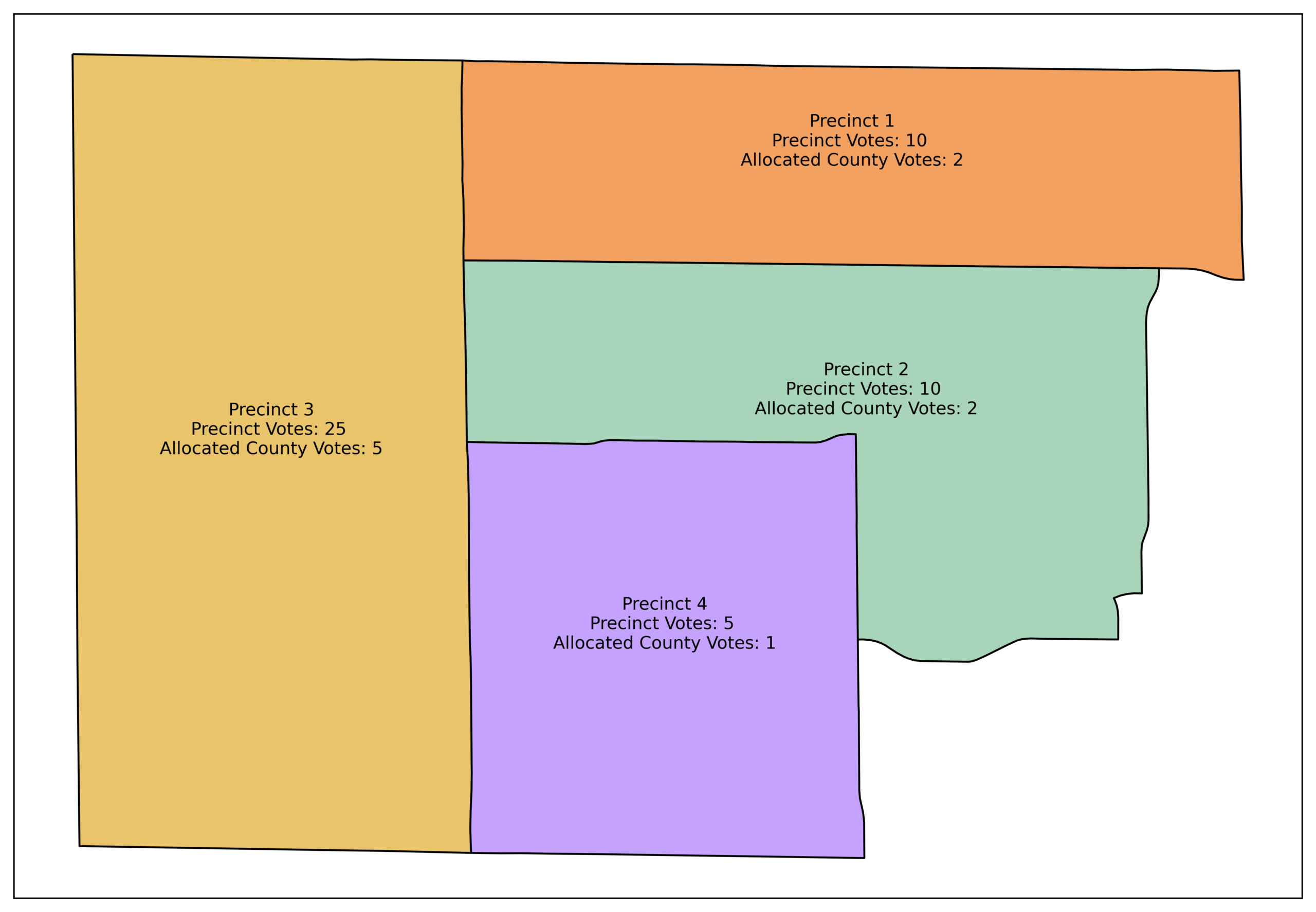

Since we don’t know the number of voters in each precinct whose votes were counted at the county level, we can use the next best available information: the number of votes cast in each precinct that were counted at the precinct level. These votes are candidate-specific, and so the allocation of votes will vary across candidates and contests in the same precinct.

In addition, to ensure that the number of county level votes allocated to precincts sums to the same total before and after allocation, we turn this data into a percent. The percent of precinct level votes for a candidate as a function of all precinct level votes in the county for that candidate is then multiplied with the number of county level votes for that candidate, to determine the number of votes to be allocated to each precinct.

For example, imagine a candidate received 50 precinct-level votes across 4 Precincts: 10 in Precincts 1 and 2, 25 in Precinct 3, and 5 in Precinct 4. Imagine they also received 10 early or absentee votes that were reported at the county level. Since the candidate received 50% of their precinct level votes in Precinct 3 (25 votes in Precinct 3 / 50 total precinct-level votes = .50), half of the county level votes should be allocated to this Precinct (50% of 10 votes = 5 votes). Similarly, the candidate received 20% of their precinct level votes each in Precincts 1 and 2 (10 votes / 50 total votes = .20), and so 20% of the 10 county wide votes should be allocated to each Precinct (2 votes each). Finally, the candidate received 10% of their precinct level votes from Precinct 4 (5 votes / 50 total votes = .10) and therefore 10% of the county level votes – that is, the remaining vote yet to be allocated – should be allocated to this Precinct.

An Example of Vote Allocation Based on Precinct Level Votes

This is a stylized example, and it is common to calculate fractional votes for allocation. Because it is not possible to have fractional votes in a real election, we use a method of rounding to integers that preserves the correct total number of votes. This method is called the Hamilton method, and is more well known for its prior use in congressional apportionment.

It’s also worth noting that some precincts are split by districts. In these cases, allocation is still done using the precinct’s share of the total precinct level votes. The fact that only some of the voters in that precinct cast a ballot in one of the districts means that the county-wide share of precinct level votes in that precinct will already be smaller than it might otherwise be, and no additional adjustments to the allocation process are necessary.

Assumptions in Vote Allocation

By using each precinct’s share of the total precinct level votes cast in a county for a particular candidate to allocate county level votes, we assume that the rate of casting a ballot counted at the precinct level relative to the rate of casting a ballot counted at the county level is constant across all precincts for a particular candidate. In other words, if a precinct with 5 votes for a particular candidate is allocated 1 vote, then a precinct with 10 votes for this candidate will be allocated 2 votes, a precinct with 20 votes will be allocated 4 votes, and so on.

It is important to understand that this assumption is not always correct – some precincts will have higher rates of votes that are counted at the county level than others, even if their number of precinct level votes counted is the same. For example, rates of absentee and early voting may vary by voters’ ease of access to a polling location or by other socioeconomic/geographic factors. The more this assumption is incorrect, the more likely it is that unexpected results post-allocation will occur.

One way in which unexpected results manifest as a result of this assumption is when there are more votes than reported voters in a particular precinct. For example, it is possible (though unlikely) that Precinct 1 had 100% turnout, and all 10 eligible voters cast a ballot that was counted at the precinct level. By assuming that the ratio of votes to be allocated to each precinct is constant, any and all precincts with precinct level votes will be allocated county level votes, including Precinct 1. As a result, Precinct 1 would have more votes recorded than voters. Summing the post-allocation votes across all precincts in a county, the total number of votes will be correct, but individual precincts may reveal such oddities. Unfortunately, the assumption that leads to these results is only verifiable if the county or state provides precinct level turnout data, which is not common.

A rare but unexpected result that can also occur is for a contest at the top of the ticket to receive fewer votes at the precinct level post-allocation than a down-ballot contest. Typically, candidates at the top of the ticket, such as those running in a Presidential race, almost always receive more votes combined than down-ballot contests, such as those running in congressional race. If a particular precinct records a proportionally larger share of all the precinct level votes in a county for a down-ballot contest than one that’s at the top of the ticket, the post-allocated votes totals may show more votes for the down-ballot contests.

A simplified example can help illuminate how this situation might occur. Imagine that a precinct recorded 10 votes for a presidential candidate A, 10 votes for presidential candidate B, 8 votes for congressional candidate A, and 8 votes for congressional candidate B. Prior to allocation, there are 20 votes cast in this precinct for the presidential contest, and 16 votes cast in the congressional contest.

Now imagine that at the county level, there are 20 votes for presidential candidate A, 20 for presidential candidate B, 16 votes for congressional candidate A, and 16 for congressional candidate B. These votes need to be allocated across all the precincts in the county.

Finally, imagine that the votes for both presidential candidates in this precinct make up 10% of all the precinct level votes in the county, and therefore each presidential candidate should be allocated 4 votes (20% of 20 county level votes). This results in 28 votes counted in this precinct post-allocation for the presidential contest (10+4 = 14 for candidate A, and 10+4 = 14 for candidate B).

However, the votes for both congressional candidates in this precinct make up 50% of all the precinct level votes in the county. Each congressional candidate should be allocated 8 votes (50% of 16 county level votes). The end result is 32 total votes counted in this precinct post–allocation for the congressional candidates (8+8 = 16 for candidate A, and 8+8 = 16 for candidate B).

Although this might occur in a single precinct, the total votes across all precincts in a county for a down-ballot contest are usually still less than the total votes for a contest at the top of the ticket. If all 10 precincts in this county had the exact same distribution of precinct level votes for the presidential and congressional candidates (10 and 8, respectively), then the presidential contest would still record 240 total votes post-allocation, and the congressional contest would have 192 votes post-allocation.

Questions about vote allocation?

Our help desk team is here to help.

Send a message and they will respond within one business day!