Florida 2012 Redistricting

A primer on the first case in which a state court struck down a redistricting plan as a partisan gerrymander

In 2010, the citizens of Florida rallied behind two proposed amendments to the state’s constitution, written by Ellen Freidin of Fair Districts Florida. With over 63% of the vote, Floridians codified the “Fair Districts Amendments,” which put in place two tiers of standards regulating how the Legislature could redistrict for both state legislative and congressional reapportionment.

Fair Districts Amendments Outlined

Fla. Const. art III, § 20

Tier 1

Tier 1 prescribed that:

Tier 2

Subordinate to the tier 1 standards were three tier 2 standards, which had to be followed unless doing so would conflict with any tier 1 standard or federal regulation, including the Voting Rights Act:

Despite strong early opposition to the amendments, Florida’s Legislature pledged to conduct an “open, interactive and inclusive redistricting process,” which included consideration of “comments and suggestions gathered from the public.”1 The Florida House and Senate each created a public mapping tool through which Floridians could draw and submit their own district maps using the 2010 Census data, giving citizens the opportunity to participate in the redistricting process and use “the same redistricting data and application[s] used by legislators and staff.”2 The public submitted 175 redistricting plans and gave 1,600 statements during a series of public hearings across the state.

1“The Florida Senate: Redistricting.” The Florida Senate, www.flsenate.gov. Accessed 3/10/2021

2“The Florida Senate.” About Redistricting – The Florida Senate, www.flsenate.gov

In February of 2012, the Legislature passed the House, Senate, and congressional maps with overwhelming bipartisan majorities.

One week later the congressional map was approved by the Governor and enacted. The state legislative maps could not immediately be enacted, however — the Florida Constitution requires that the Florida Supreme Court conduct a thirty day review of the Senate and House plans to determine whether the plans comply with the state’s constitution (see Article III, § 16(c). Fla. Const).3 Although the Court had conducted such a review on past redistricting plans, this was the first review which considered compliance with the new Fair Districts Amendments.

3This was added in 1968 to allow expedited review by the state Supreme Court, given that legal challenges over apportionment plans are inevitable.

This review led to two important findings: First, the Court recognized that the tier-one standard regarding minorities was written to mimic Sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). As such, the Court’s review would follow the U.S. Supreme Court’s judicial precedent on the VRA — the Florida Courts would use the same test for minority vote dilution used by the Supreme Court (the Gingles preconditions of Section 2) and would assess whether retrogression (the diminishment of a minority group’s ability to elect candidates of their choosing) occurred in any district, regardless of whether the district was a federally covered jurisdiction.4

4The Fair Districts Amendments’ equivalent of Section 2 is “districts shall not be drawn with the intent or result of denying or abridging the equal opportunity of racial or language minorities to participate in the political process.” The Fair Districts Amendments’ equivalent of Section 5 is “districts shall not be drawn with the intent or result … to diminish [racial or language minorities’] ability to elect representatives of their choice.”

In order to demonstrate that the minority voting strength had not been diluted and that retrogression had not occurred, the Court required that a comprehensive “functional analysis” be performed. Apportionment I5 at 67. This included analysis of Racially Polarized Voting (RPV) and consideration of:

- voting-age populations

- voting-registration data

- voting registration of actual voters

- election results history

5In re Senate Joint Resol. of Legislative Apportionment 1176, 83 So. 3d 597, 599 (Fla. 2012)

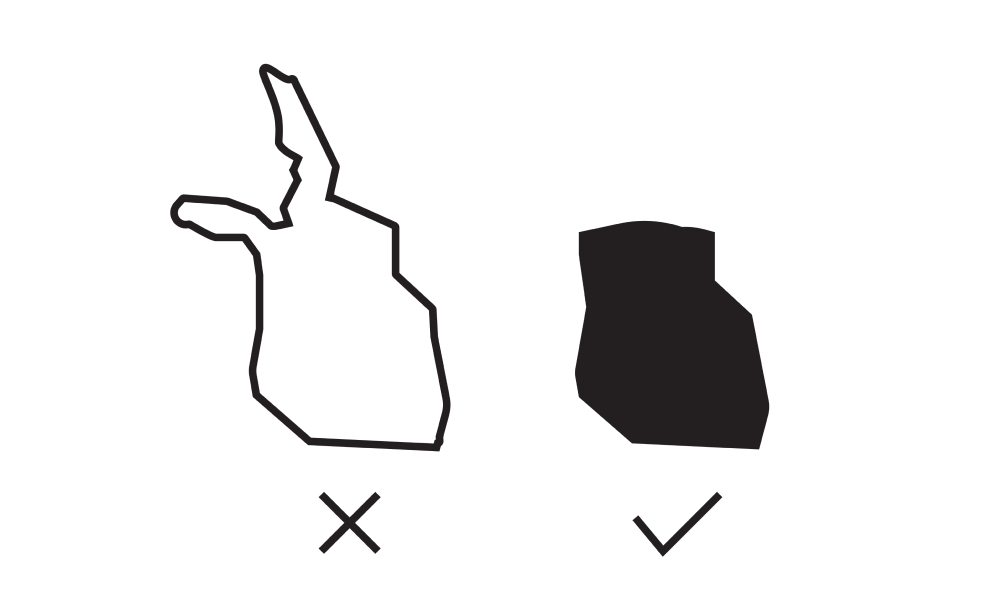

Second, the Court determined that Legislative intent could be inferred by how well the Legislature had complied with the tier 2 standards of compactness, equal population, and utilizing existing political and geographic boundaries. This determination was critical because the Fair Districts Amendments prohibited drawing maps with the intent, but not effect, of favoring a political party or incumbents.

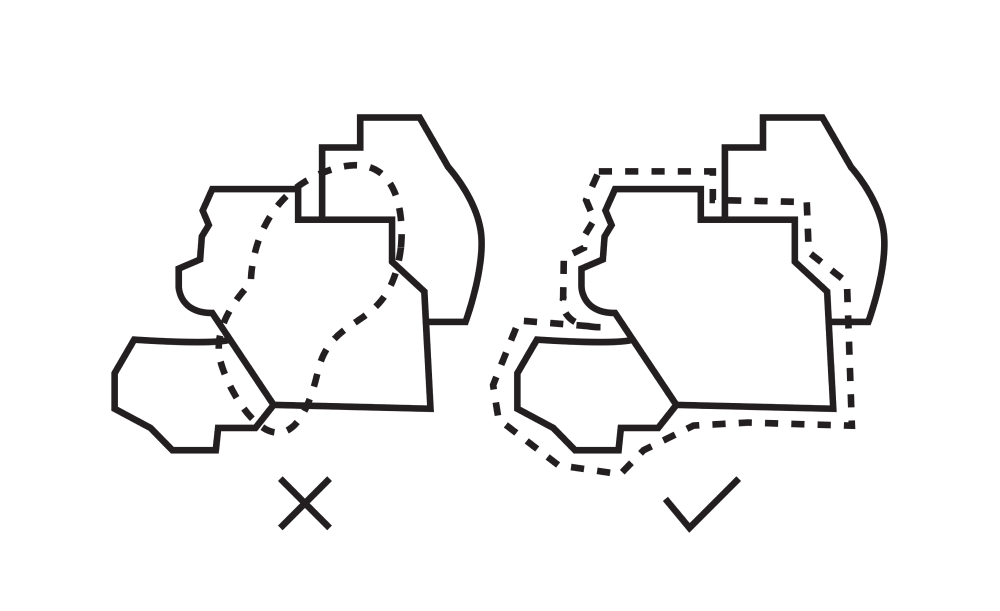

To assess whether the Legislature’s maps complied with the tier 2 standards — and thus infer the Legislature’s intent — the Court reviewed alternative maps submitted by the nonpartisan Fair Districts Coalition, a group composed of the League of Women Voters, the National Council of La Raza, and Common Cause Florida, as well as the Florida Democratic Party. Relying on an idea from the Department of Justice, the Court looked at whether any “alternative or illustrative plans … [made] the least departure from [Florida’s] stated redistricting criteria.” In instances where the alternative maps were more compliant with the tier 2 standards than was the Legislature’s map, the Court pressed the Legislature to demonstrate that its lack of tier 2 compliance was a result of an effort to comply with a more important tier 1 standard, such as not diminishing minorities’ voting power. When the Legislature could not do so, impermissible intent to favor a political party or incumbents was inferred. In the Court’s words:

Where it can be shown that it was possible for the Legislature to comply with the tier 2 constitutional criteria while, at the same time, not diminishing minorities’ ability to elect representatives of choice or denying minorities an equal opportunity to participate in the political process, the Legislature’s plan becomes subject to a concern that improper intent was the motivating factor for the design of the district …. Where adherence to a tier 2 requirement explains the irregular shape of a given district, a claim that the district has been drawn to favor or disfavor a political party can be defeated. Where it does not, however, further inquiry into the Legislature’s intent becomes necessary.

Using this framework, the Court ruled that the House map was constitutionally valid but the Senate map was constitutionally invalid. The Court rejected the Senate map on the basis that it was drawn with the intent to favor a political party and incumbents, a violation of a tier 1 standard, and consistently neglected the tier 2 standards of equal population, compactness, and utilizing political and geographic boundaries.

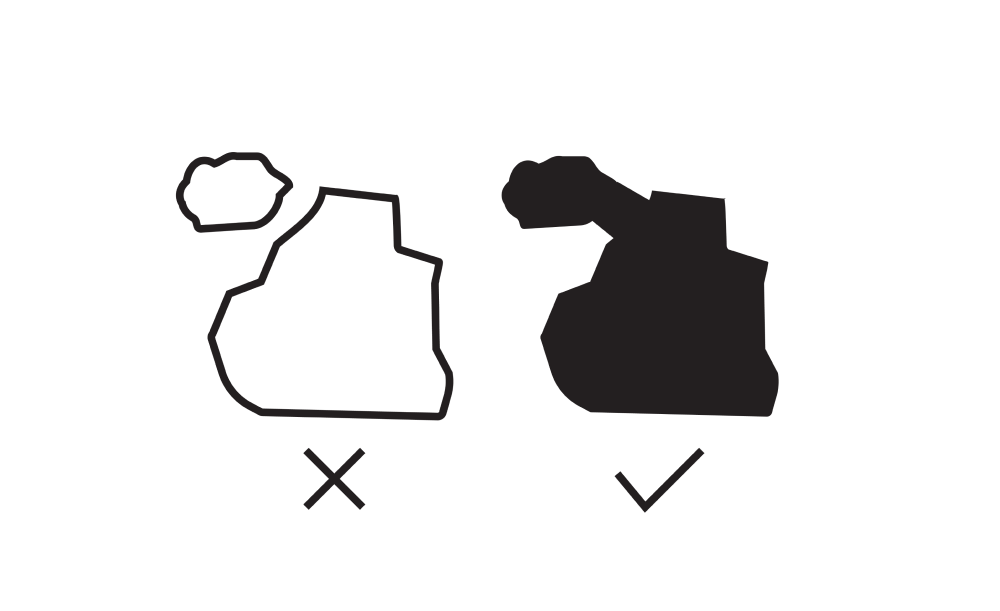

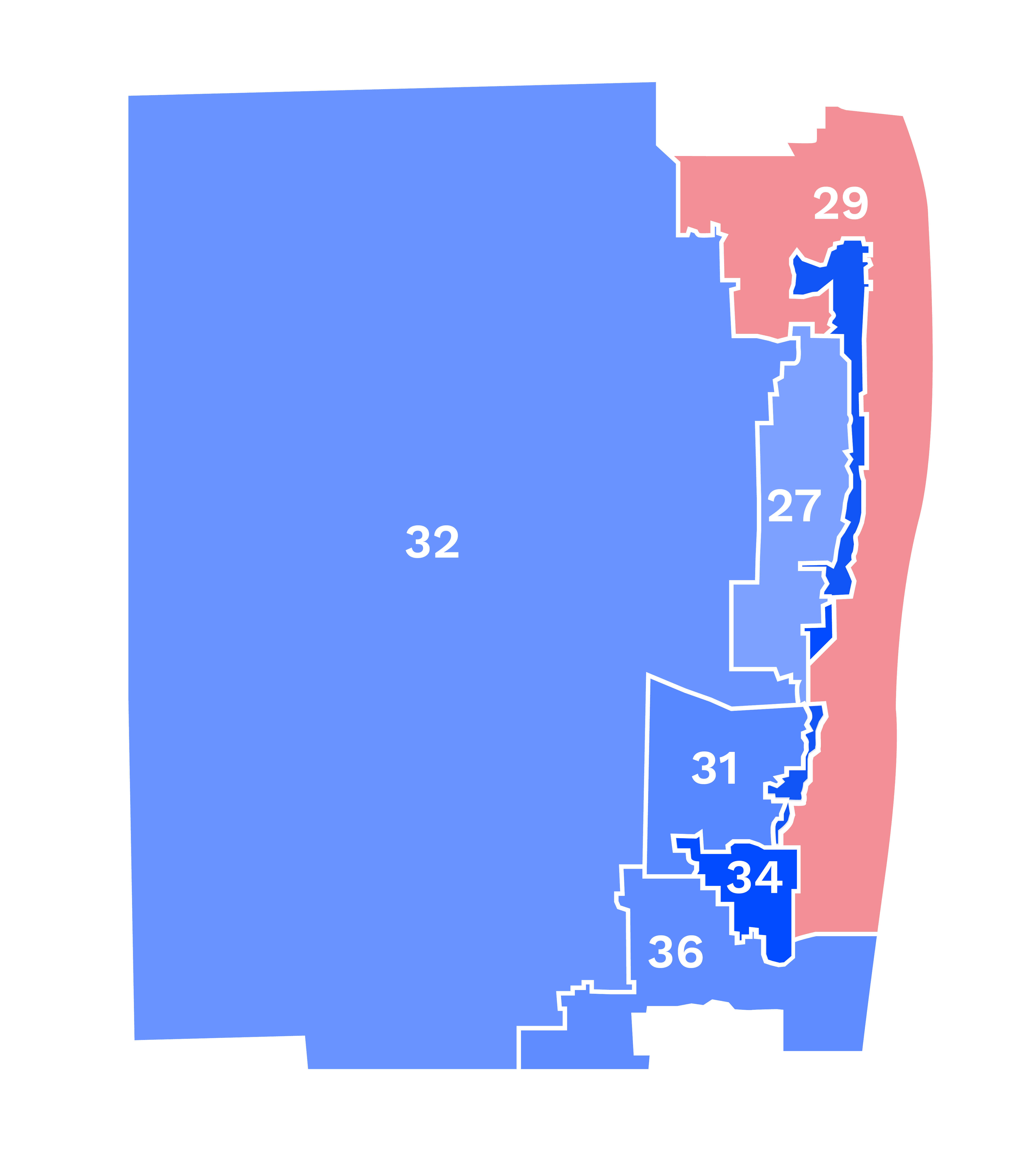

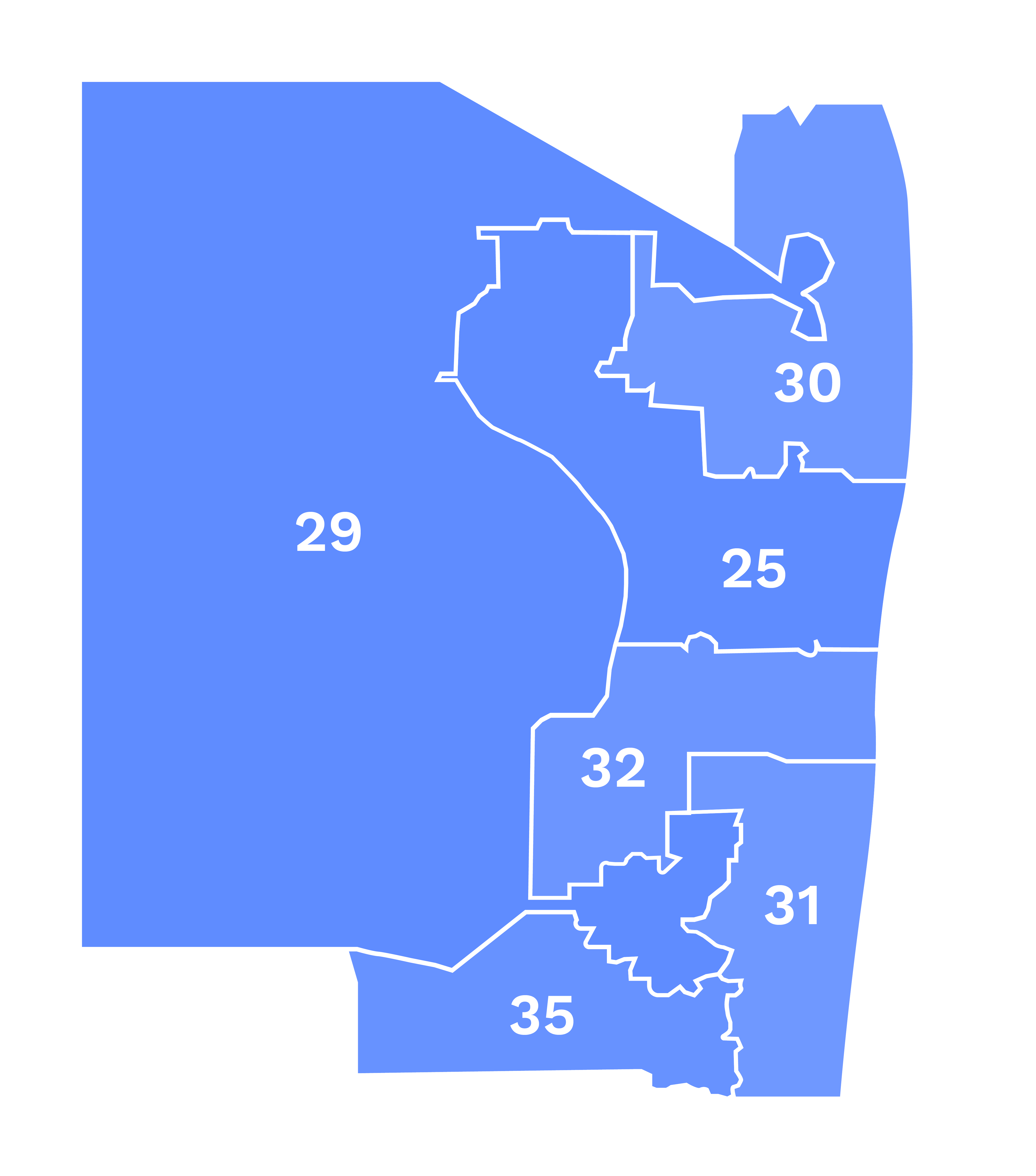

A number of specific districts contributed to this ruling. Senate Districts 29 & 34 (D29 and D34), pictured below, were among these, and are exemplars of how tier 2 assessment was used to illustrate Legislative intent.

| Map Metric | District 29 | District 34 |

|---|---|---|

| BVAP | 6.6% | 55.8%6 |

| Reock Compactness | 0.15 | 0.05 |

| Area/Convex Hull Compactness | 0.56 | 0.25 |

BVAP and compactness scores of Senate Districts 29 and 34. District 34 was purportedly designed only with the intent to perform for Black voters.

6BVAP values from Appendix-Petition, Feb. 2, 2012, submitted by Pamela Jo Bondi to the Fla. Supreme Court, In Re Senate Joint Resolution of Legislative Apportionment 1176.

Both districts scored extremely poorly on the Reock and Area/Convex Hull compactness metrics.7 According to the Senate, District 29, had a justifiably low compactness score because it had to conform to the shape of District 34, and because it connected coastal communities together in one district.8

7A Reock score measures the ratio of a district’s area to the smallest circle that inscribes the district. Area/Convex Hull measures the ratio of a district’s area to the smallest convex polygon that inscribes the district. Both metrics range from 0 to 1, with 1 being the most compact.

8Apportionment I at 169

The Senate argued that District 34 had a justifiably low compactness score because it connected neighborhoods with high concentrations of Black voters, ostensibly to create a district that would give Black voters the opportunity to elect candidates of their choosing, thereby complying with the Fair Districts Amendments. Together, these neighborhoods produced a district with a Black Voting Age Population (BVAP) of 55.8%.

However, the Senate did not analyze whether the district would actually perform for these Black voters — in fact, the Senate did not analyze whether racially polarized voting existed in the region, nor whether Black voters would in fact control the primary or general election of the district. Instead, the Senate preserved “the core of a district that ha[d] consistently elected candidates preferred by minority voters” — District 34 maintained 79.4% of its predecessor 2002 district.9 Ibid at 168, quoting Senate District Descriptions at 1014.

9On average, districts in the map maintained 64.2% of their predecessor 2002 districts. In re Senate Joint Resol. of Legislative Apportionment 1176, 83 So. 3d 597, 599 (Fla. 2012) at 124.

According to the Senate, it had not performed these analyses because doing so would have required election results data and voter registration data, and the Senate purportedly believed that “the mere presence of political metrics… for building districts could create a perception, unsubstantiated and inaccurate though it may be, that partisan factors influenced how districts were drawn.” Ibid at 33.

However, this decision was at odds with the precedent set by the U.S. Supreme Court and the Department of Justice in past voting rights cases, and now went against Florida’s own Supreme Court, which stated that using this data was necessary to ensure compliance with the Fair Districts Amendments. Instead, the Senate simply found one district configuration that produced a majority BVAP, but did not assess whether there were more tier 2 compliant configurations that also afforded Black voters the opportunity to elect a candidate of their choosing. In other words, the Senate had failed to “conduct a functional analysis… in order to properly determine when, and to what extent, tier 2 requirements must yield.” Ibid at 130.

In reviewing District 34, the Court considered two salient questions:

- would the Senate’s district actually perform for Black voters? – if not, then there was no justification for its extremely poor compactness scores

- if the district would perform for Black voters, was the Senate’s configuration the most tier 2 compliant way to create a Black-performing district?

If both these questions were answered affirmatively by the Court, the district would be declared valid, as it offered Black voters the opportunity to elect a candidate of their choosing, and did so in the most tier 2 compliant manner. If, however, a more compact configuration existed that simultaneously performed for minority Black voters, the Court would assume that the Legislature had neglected this configuration in the pursuit of protecting a political party or an incumbent.

An analysis performed by the Court showed that District 34 would in fact perform for Black voters: 67.7% of voters in the district were registered Democrats, and 67% of these Democrats were Black. Coupled with a RPV analysis showing that 85.2% of Black voters were Democrats, it was sufficiently clear that Black voters voted cohesively for Democrats, would control the Democratic primary, and would likely elect the candidate of their choosing.10 The Court’s first question had been answered affirmatively.

10Apportionment I at 168, footnote 55

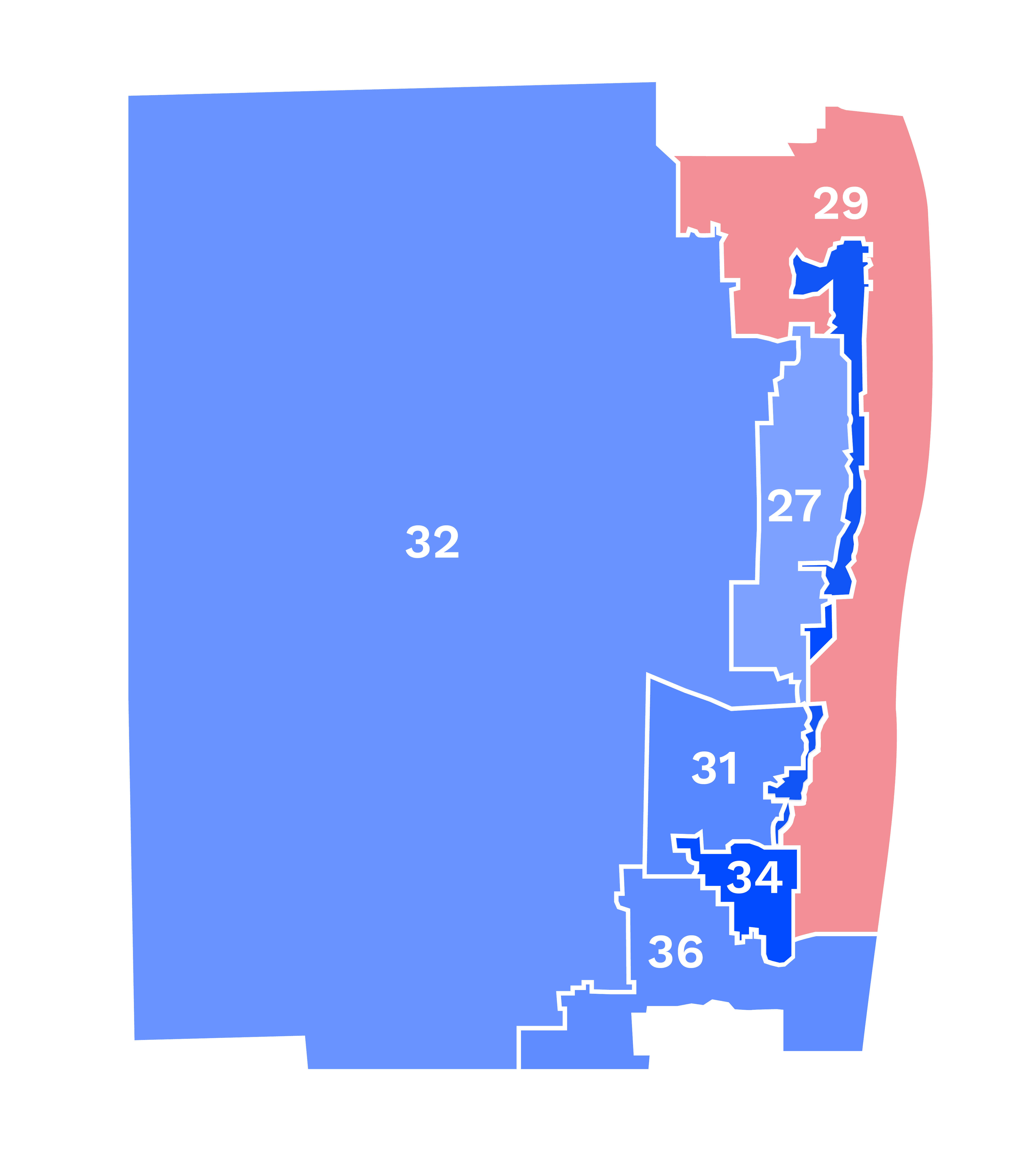

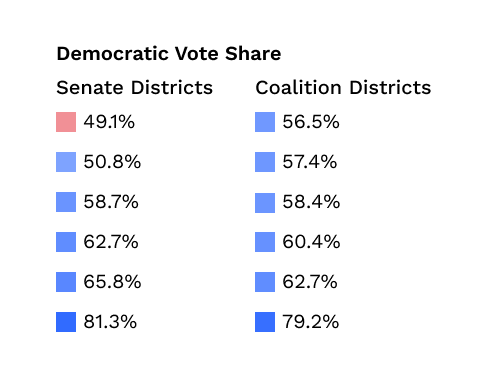

In answering question 2, the Court not only looked at the Senate’s district configuration, but also considered the map provided by the Coalition. The Coalition’s map, pictured above, reconstructed this area far more compactly. Importantly, it also maintained a district that would perform for Black voters. District 29 in the Coalition map had a BVAP of 55.7%. An analysis performed by the Coalition and the Court showed that in District 29, 68.3% of voters were registered Democrats, 65.5% of registered Democrats were Black, and 85.1% of registered Black voters were Democrats, suggesting that Black voters would vote as a bloc and thus determine the outcomes of both the Democratic primary and the general election.11 The Coalition also assessed the district under the 2006 and 2010 gubernatorial elections and the 2008 presidential election and found that the candidates preferred by Black voters would have won with at least 75% of the vote.

11Apportionment I at 171, footnote 59.

According to the Court, “the Coalition’s plan demonstrate[d] that the Senate was able to draw districts in this region of the state to better comply with Florida’s compactness requirement while, at the same time, maintaining a black majority-minority district.” (Apportionment I at 173). The Court’s second question had been answered — a more tier 2 compliant district existed that would still give Black voters the opportunity to elect a candidate of their choice. Why, then, had the Senate failed to propose this more compliant configuration?

Hidden in the Senate’s poor compactness scores was a partisan end. In the Senate’s plan, District 34, the Black majority-minority district, was overwhelmingly Democratic, voting for the Democratic candidate by greater than 77% in the 2006 gubernatorial, 2008 presidential, and 2010 gubernatorial elections. Ibid at 168. Indeed, every district surrounding District 34 performed Democratic, except for District 29. District 29 was competitive but leaned Republican based on the 2010 and 2006 gubernatorial elections and the 2008 presidential election. The Republican candidate would have won two of those three elections.

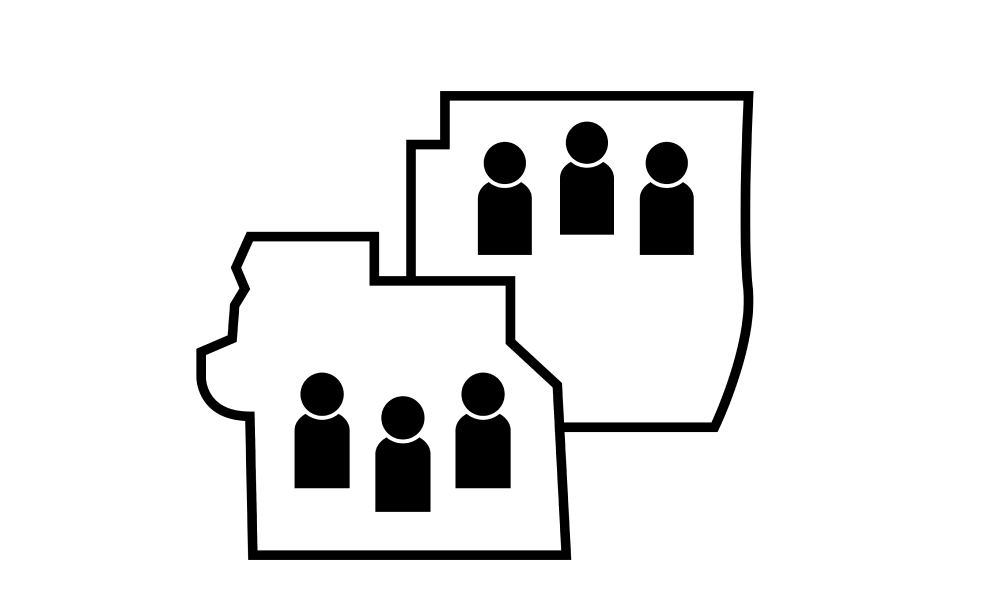

When compared to the Coalition’s plan, the political performance of the Senate’s District 29 in an otherwise Democratic area suggested an intentional manipulation of district boundaries to produce one Republican district. By reconfiguring this area to produce far more compact districts, the Coalition concomitantly produced districts that were all Democratic performing. Democratic voters who had been concentrated in Senate District 34 were dispersed into the surrounding districts, including Senate District 29 — this dispersion reduced the Republican performance of the district, yielding an additional Democratic district.

The Court considered the partisan breakdown of the Coalition’s configuration a more natural and nonpartisan configuration of the area because Democratic voters in the region were concentrated and the area was largely Democratic: the Coalition’s plan appeared to be the result of an effort to “draw logical, compact districts in a neutral manner.” Ibid at 174.

Because the Senate was unable to justify why it had chosen its non-compact configuration over a more compact — and therefore more compliant — configuration, the Court inferred that the improved Republican performance in D29 had motivated the Senate’s decisions. This violated the tier 1 standard prohibiting mapping with the intent to favor a political party, and therefore the Court invalidated the district.

This decision reveals two critical points: First, the Coalition’s alternative map played a central role in providing circumstantial evidence of impermissible partisan intent. By supplying the Court with a significantly more compliant map, the Coalition showed that the Legislature must have had an unstated ulterior motive. Second, the use of election results and voter registration data allowed the Coalition to prove that its configuration would provide Black voters the ability to elect a candidate of their choice, and that the Senate’s configuration packed Democratic voters into one district to improve the Republican performance of a neighboring district.

Eight total districts were found to be unconstitutional under similar analyses.

Incumbent Protections

In addition to the districts themselves being unconstitutional, the district renumbering scheme employed by the Senate was found unconstitutional. Generally, Florida Senators are limited to eight consecutive years in office — two four-year terms. However, all Florida Senators are put up for election following a redistricting year. In order to maintain staggered Senate terms (which is mandated in the Florida constitution) some Senators are elected for a two year term following a redistricting year (the other Senators are up for election 4 years after the redistricting year). When this occurs, a Senator may have the opportunity to also serve two four-year terms in addition to this two year term, for a total of ten years in office. Depending on a Senator’s district number, he or she may get elected for one of these shortened two-year terms.

In an early plan proposed by the Senate Reapportionment Committee, the district numbers used in the 2002 map were carried over to the new map; this numbering gave (by chance) at most 10 of the 29 non-term limited Senators the option to serve for ten consecutive years in office. One month after that plan emerged, the Committee published a substitute plan, under which 39 of 40 districts were given a new number. The result was that 28 of the 29 non-term-limited incumbents were eligible for ten-year terms. By simply changing district numbers, the Senate was able to give most incumbents the opportunity to be elected for ten years, rather than the typical eight. The Court was able to verify these facts because the Coalition had supplied the addresses for a majority of these non-term limited Senators. By overlaying these addresses on the Senate map, it was apparent that the renumbering of the districts had been designed to give incumbents the opportunity to serve longer terms. This was a clear violation of the prohibition on mapping with the intent to favor incumbents.

After the Court declared the Senate map unconstitutional, the Legislature reconvened to fix the map. The invalidated districts were modified to redress the unconstitutional features of the map and were then renumbered. After the remedial plan was passed by the Legislature, the Court reviewed the plan. This time, in April of 2012, the Court determined that the Legislature had complied with the Fair Districts Amendments, and the map was enacted.

Circuit Court Challenges

Soon after, the Coalition issued challenges to the congressional map, which had yet to be challenged, and the revised Senate map, contending that both had been drawn in contravention to the Fair Districts Amendments. Two suits were opened, one against each map, in the Florida Circuit Courts. Although the Supreme Court had already declared the revised Senate map valid, it allowed the circuit court to hear the case. Because the Florida Constitution only allotted 30 days for the Supreme Court’s original review, that Court had limited itself to a “facial determination based on… undisputed data” that could be derived directly from the map, such as compactness scores, district populations, adherence to existing borders, and so on. API at 203, emphasis added. The circuit court’s case would be markedly different because it would have the time to review as-applied challenges, which include witness testimony and evidence produced through a discovery process.

The two cases proceeded in parallel for a number of months. In September of 2012, a lengthy and bitter discovery process opened in the congressional case. The Coalition began looking into a series of consultants who had ties to a number of high-ranking members of the Florida Legislature, including Speaker of the House Dean Cannon (R), Senate Reapportionment Committee Chairman Don Gaetz (R), and Chairman of the House Redistricting Committee Will Wetherford (R). The consultants had histories of working on maps: one, Frank Terraferma, was described as a “genius map drawer”; another, Rich Heffley, had been receiving substantial payments from the Republican Party of Florida for “unspecified redistricting services.” APVIII at 23.

The Coalition issued subpoenas to four consultants: Terraferma, Heffley, Pat Bainter and Marc Reichelderfer. Reichelderfer cracked during deposition and handed over a series of communications that blew the case open. It quickly became clear that a well thought out plan had been crafted between the Legislature and the consultants, beginning in 2010.

The Record Revealed

No longer able to legally engage the services of these partisan consultants (doing so would have immediately raised flags about violating the ‘no intent to favor a party’ clause of the Fair Districts Amendments), members of the Legislature met with the four consultants in two private meetings, the first in December of 2010, just one month after the Fair Districts Amendments were codified. According to the Legislative leadership, the consultants were told at these meetings that they would not be allowed to participate in the Legislature’s redistricting process because of the new Fair Districts Amendments standards. However, the records produced from the discovery process revealed a very different story: a concerted and “surreptitious participation of partisan operatives in the apportionment process.” Apportionment V at 2.12

12League of Women Voters of Fla. v. Data Targeting, Inc, SC14-987 (Fla. 2014)

Soon after these meetings, the consultants began drafting maps of their own. They then passed these maps to third party members of the public who acted as proxies and were instructed to submit the maps through the public mapping portals, which ironically had been set up by the Legislature to help with their “open, interactive and inclusive redistricting process.” The consultants drafted scripts for people attending the public hearings that advocated for components of the consultants’ own maps. The Legislature then pulled out portions of these maps from among the many that had been submitted. In one instance, a map traced back to a consultant’s computer shared eleven identical districts with a map submitted under an alternate name, Alex Posada, through the public portal. Later, Senator Gaetz, then Chairman of the Senate Reapportionment Committee, stated that “[t]he Committee relied upon a publicly submitted map by Alex Posada… in developing District 6 boundaries.” Amos 105.

The consultants’ participation did not end there. Once the public portal closed and the Legislature started mapping, the malfeasance continued: communications produced from the discovery process showed that Legislators and their staffers were passing draft maps to the consultants for review and edits, often before the maps, if ever, were released to the public. Kirk Pepper, the Deputy Chief of Staff for Speaker Cannon, sent one of the consultants 24 draft maps, most of which had yet to be released to the public. Pepper sent them through his personal email account, a ‘Dropbox’ account he later deleted, and a thumb drive. League of Women Voters of Fla. v. Detzner, SC14-1905 (Fla. July 9, 2015).

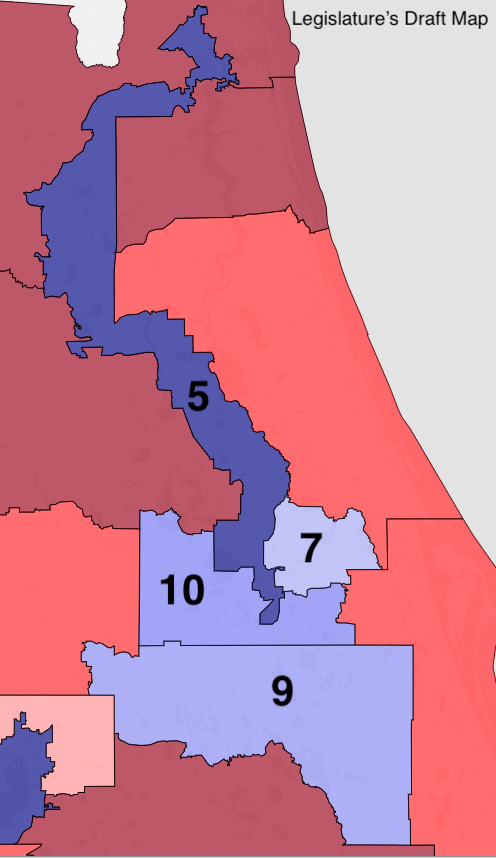

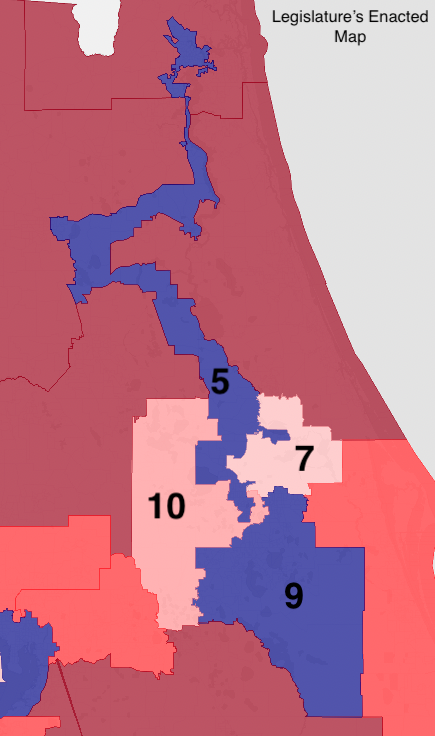

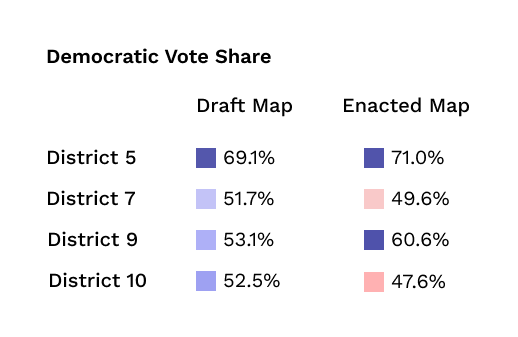

These maps were then edited by the consultants and sent back. Often, minor changes to district lines had significant partisan impacts. Take these two maps:

The first map, a draft map drawn by Legislative staffers, had four Democratic districts in Northeastern Florida, numbered and highlighted in blue to reflect their varying levels of partisanship (the darker blue a district’s color, the more Democratic it leans; the darker red, the more Republican). Before it was released to the public, Legislative staffers sent the draft map to Reichelderfer, who made a series of changes to the district borders and sent the map back. These changes were ultimately incorporated into the map enacted by the Legislature, shown on the right. By shifting district lines in small ways, the consultant took the four Democratic districts and turned them into two Democratic and two Republican districts, all while maintaining the partisanship of the abutting districts.

When details about the consultant’s influence on the map making process emerged, the Legislature was asked in court why it incorporated the conspicuously partisan changes. The Legislature responded that the changes to the districts’ boundaries were necessary to increase the Black voting age population of District 5 to comply with the Voting Rights Act, a claim that was “not supported by the evidence,” according to Judge Terry Lewis, who presided over the circuit court challenge to the map.

Many additional schemes of this kind were uncovered by the Circuit Court — and many more might have been revealed had the Legislators not systematically deleted all their own records. After the Coalition had issued subpoenas to the consultants, it had done the same to a number of Legislators, requesting communications and documents related to redistricting. Rather than comply, the Legislature claimed Legislative privilege, arguing that no Legislator could be deposed or should have to produce any documents. The claim made its way to the Florida Supreme Court, which ruled that although Legislative privilege existed (this being the first time it was claimed in the state), it was not absolute and had to yield because there was a compelling public interest that the documents might help answer: whether or not the Legislature had complied with Florida’s Constitution.

However, after the Supreme Court ordered the Legislature to release all its redistricting related documents, the Legislature had virtually nothing to produce, save a handful of draft maps. As the Supreme Court later stated, “the Legislators … systematically deleted almost all of their e-mails and other documentation relating to redistricting.” Apportionment VII, at 21.

Still, the documents produced by the consultants had been enough. Coupled with analyses of individual districts mirroring the Supreme Court’s initial review, the Circuit Court struck down the congressional map for violating the Fair Districts Amendments, although the court only noted violations in two of twenty-seven districts. The Legislature reconvened in August of 2014 and passed a remedial congressional plan, which the Circuit Court reviewed and approved.

Convinced that the circuit court’s ruling had been too forgiving to the Legislature, the Coalition appealed the case directly to the Florida Supreme Court. On review, the Supreme Court found that the Circuit Court had not gone nearly far enough – the evidence was clear that the Legislature had, as Circuit Court Judge Lewis wrote, “made a mockery of the Legislature’s proclaimed transparent and open process of redistricting” and that the entire process was “tainted by unconstitutional intent to favor the Republican Party and incumbent lawmakers.” (Lewis at 21 and APVII at 1, internal quotations omitted). The Supreme Court struck down the remedial congressional plan, citing eight districts that were unconstitutional, and ordered the Legislature to reconvene for a third time to fix the plan.

When this ruling was issued, the circuit court case for the revised Senate map had not concluded. Rather than face a repeated discovery process, the Senate decided to sign a Stipulation and Consent agreement, admitting that it had violated Florida’s Constitution:

[T]he Florida Senate stipulates and agrees that the apportionment plan adopted by the Florida Legislature on March 27, 2012, to establish Florida’s Senate districts … violates the provision of Article III, Section 21(a) of the Florida Constitution providing that ‘[i]n establishing legislative district boundaries … [n]o apportionment plan or district shall be drawn with the intent to favor or disfavor a political party or an incumbent,’ because the Enacted Senate Plan and certain individual districts were drawn to favor a political party and incumbents.”

The Legislature reconvened for special sessions in August and October of 2015 to produce remedial congressional and Senate maps, respectively. However, infighting between the two chambers and between two factions of Senate Republicans hindered their work — both special sessions adjourned without the adoption of remedial maps.

The cases returned to their respective Circuit Courts. The courts accepted potential maps from both chambers of the Legislature, as well as a number of alternative maps from the Coalition and the Florida Democratic Party. But rather than merely using the alternative maps as comparators, the Supreme Court ordered the Circuit Courts to review all the maps and determine which one best complied with the U.S. and Florida Constitutions. Whichever map was best would be enacted, even if it was not drawn by the Legislature.

In both cases, a map presented by the nonpartisan Fair Districts Coalition was found to be the most compliant. Much to the chagrin of the Legislature, the Coalition’s maps were enacted and were used beginning in the 2016 election. These maps are still in place today.

Do you have any questions?

Our help desk team can answer your questions about redistricting data and the redistricting process. Send a message and they will respond within one buisness day!

Send a message